For some of your Python applications, a plugin architecture could really help you to extend the functionality of your applications without affecting the core structure of your application. Why would you want to do this? Well, it helps you to separate the core system and allows either yourself or others to extend the functionality of the core system safely and reliably.

Some of the advantages include that when a new plugin is created, for example, you would just need to test the plugin and the whole application. The other big advantage is that your application can grow by your community making your application even more appealing. Two classic examples are the plugins for WordPress blog and the plugins for Sublime text editor. In both cases, the plugins enhance the functionality of the core system but the core system developer did not need to create the plugin.

There are disadvantages too however with one of the main ones being that you can only extend the functionality based on the constraints that is imposed on the plugin placeholder e.g. if an app allows plugins for formatting text in a GUI, it’s unlikely you can create a plugin to play videos.

There are several methods to create a plugin architecture, here we will walkthrough the approach using importlib.

The Basic Structure Of A Plugin Architecture

At it’s core, a plugin architecture consists of two components: a core system and plug-in modules. The main key design here is to allow adding additional features that are called plugins modules to our core system, providing extensibility, flexibility, and isolation to our application features. This will provide us with the ability to add, remove, and change the behaviour of the application with little or no effect on the core system or other plug-in modules making our code very modular and extensible

The Core System

The core system defines how it operates and the basic business logic. It can be understood as the workflow, such as how the data flow inside the application, but, the steps involved inside that workflow is up to the plugin(s). Hence, all extending plugins will follow that generic flow providing their customised implementation, but not changing the core business logic or the application’s workflow.

In addition, it also contains the common code being used (or has to be used) by multiple plugins as a way to get rid of duplicate and boilerplate code, and have one single structure.

The Plug-in Modules

On the other hand, plug-ins are stand-alone, independent components that contain, additional features, and custom code that is intended to enhance or extend the core system. The plugins however, must follow a particular set of standards or a framework imposed by the core system so that the core system and plugin must communicate effectively. A real world example would be a car engine – only certain car engines (“plugins”) would fit into a Toyota Prius as they follow the specifications of the chassis/car (“core system”)

The independence of each plugin is the best approach to take. It is not advisable to have plugins talk to each other, unless, the core system facilitates that communication in a standardized way so that independent plugins can talk to each other. Either way, it is simpler to keep the communication and the dependency between plug-ins as minimal as possible.

Building a Core System

As mentioned before, we will have a core system and zero or more plugins which will add features to our system, so, first of all, we are going to build our core system (we will call this file core.py) to have the basis in which our plugins are going to work. To get started we are going to create a class called “MyApplication” with a run() method which prints our workflow

#core.py

class MyApplication:

def __init__(self, plugins:list=[]):

pass

# This method will print the workflow of our application

def run(self):

print("Starting my application")

print("-" * 10)

print("This is my core system")

print("-" * 10)

print("Ending my application")

print() Now we are going to create the main file, which will import our application and execute the run() method

#main.py

# This is a main file which will initialise and execute the run method of our application

# Importing our application file

from core import MyApplication

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Initialising our application

app = MyApplication()

# Running our application

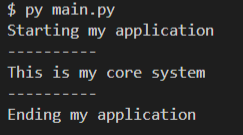

app.run() And finally, we are run our main file which result is the following:

Once that we have a simple application which prints it’s own workflow, we are going to enhance it so we can have an application which supports plugins, in order to perform this, we are going to modify the __init__() and run() methods.

The importlib package

In order to achieve our next goal, we are going to use the importlib which provide us with the power of implement the import statement in our __init__() method so we are going to be able to dynamically import as many packages as needed. It’s these packages that will form our plugins

#core.py

import importlib

class MyApplication:

# We are going to receive a list of plugins as parameter

def __init__(self, plugins:list=[]):

# Checking if plugin were sent

if plugins != []:

# create a list of plugins

self._plugins = [

# Import the module and initialise it at the same time

importlib.import_module(plugin,".").Plugin() for plugin in plugins

]

else:

# If no plugin were set we use our default

self._plugins = [importlib.import_module('default',".") .Plugin()]

def run(self):

print("Starting my application")

print("-" * 10)

print("This is my core system")

# We is were magic happens, and all the plugins are going to be printed

for plugin in self._plugins:

print(plugin)

print("-" * 10)

print("Ending my application")

print() The key line is “importlib.import_module” which imports the package specified in the first string variable with a “.py” extension under the current directory (specified by “.” second argument). So for example, the file “default.py” which is present in the same directory would be imported by calling: importlib.import_module('default', '.')

The second thing to note is that we have “.Plugin()” appended to the importlib statement: importlib.import_module(plugin,".").Plugin()

This (specifically the trailing brackets Plugin() is present) to create an instance of the class and store it into _plugins internal variable.

We are now ready to create our first plugin, the default one, if we run the code at this moment it is going to raise a ModuleNotFoundError exception due to we have not created our plugin yet. So let’s do it!.

Creating default plugin

Keep in mind that we are going to call all plugins in the same way, so files have to be named as carefully, in this sample, we are going to create our “default” plugin, so, first of all, we create a new file called “default.py” within the same folder than our main.py and core.py.

Once we have a file we are going to create a class called “Plugin“, which contains a method called process. This can also be a static method in case you want to call the method without instantiating the calls. It’s important that any new plugin class is named the same so that these can be called dynamically

#deafult.py

# Define our default class

class Plugin:

# Define static method, so no self parameter

def process(self, num1,num2):

# Some prints to identify which plugin is been used

print("This is my default plugin")

print(f"Numbers are {num1} and {num2}") At this moment we can run our main.py file which will print only the plugin name. We should not get any error due to we have created our default.py plugin. This will print out the module (from the print statement under the MyApplicaiton.run() module) object itself to show that we have successfully imported out the plugin

Let’s now modify just one line in our core.py file so we call the process() method instead of printing the module object

#core.py

import importlib

class MyApplication:

# We are going to receive a list of plugins as parameter

def __init__(self, plugins:list=[]):

# Checking if plugin were sent

if plugins != []:

# create a list of plugins

self._plugins = [

importlib.import_module(plugin,".").Plugin() for plugin in plugins

]

else:

# If no plugin were set we use our default

self._plugins = [importlib.import_module('default',".").Plugin()]

def run(self):

print("Starting my application")

print("-" * 10)

print("This is my core system")

# Modified for in order to call process method

for plugin in self._plugins:

plugin.process(5,3)

print("-" * 10)

print("Ending my application")

print() # Output $ py main.py Starting my application This is my core system This is my default plugin Numbers are 5 and 3 Ending my application

We have successfully created our first plugin, and it is up and running. You can see the statement “This is my default plugin” which comes from the plugin default.py rather than the main.py program.

Let’s create two more plugins which provides multiplication and addition to show the extensibility of plugins can work. Please note, that in the following example, you do not need to make any changes to core.py! You simply need to add plugin files.

Adding new features (plugins)

In order to add these features, we are going to build two new files, one named “addition.py” and the order called “multiplication.py“, just remember that the class within each file has to be named as “Plugin” and the static method should be named “process“. Once we have these implementations we are going to be able to modify or add functionality to the core system without modifying it.

# addition.py file

# Each new plugin class has to be named Plugin

class Plugin:

# This is the feature offer by this plugin.

# it prints the result of adding 2 numbers

def process(self, num1, num2):

print("This is my addition plugin")

print(num1 + num2) # multiplication.py file

# Each new plugin class has to be named Plugin

class Plugin:

# This is the feature offer by this plugin.

# it prints the result of multiplying 2 numbers

def process(self, num1, num2):

print("This is my multiplication plugin")

print(num1 * num2) Before we run our new plugins we are going to use a library called “sys” which allow us to receive parameters from the CLI (see our article: How to use argv in python), this way we are going to be able to indicate which plugin we are going to call within our application.

Our director has the following files:

+ main.py

+ core.py

+ default.py

+ addition.py

+ multiplication.py# main.py

# Import the sys library

import sys

from core import MyApplication

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Initialize our app with the parameters received from CLI with the sys.argv

# Starts from the possion one due to position 0 will be main.py

app = MyApplication(sys.argv[1:])

# Run our application

app.run() # Call our main.py file # Send all 3 plugins as parameters $ py main.py default addition multiplication Starting my application This is my core system This is my default plugin Numbers are 5 and 3 This is my addition plugin 8 This is my multiplication plugin 15 Ending my application

Conclusion

We started off with two files of main.py and core.py which provided the core functionality. Without modifying these two files, we can now create new plugin files and then call that functionality with command line parameters. This provides incredible flexibility and extensibility and can help to expand your applications very easily.

The other are to be mindful of is to ensure you provide strong documentation and examples so that the community for your application knows exactly how to create new plugins. This make it easier to enrich your applications quite effectively.

Get Notified Automatically Of New Articles

Error SendFox Connection: {“message”:”Unauthenticated.”}